Generic Name: Famotidine

Brand Names: Various around the world

What is Famotidine?

Famotidine is a histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) medication used to treat and prevent various gastrointestinal conditions, such as peptic ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Famotidine side effects and uses will be extensively analysed throughout this article. Discovered in 1979 by researchers at Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. in Japan, famotidine was first marketed in 1981 under the brand name Gaster. This article will examine several medical journals and research papers that have investigated the specific active ingredient, famotidine, rather than focusing on brand names. These include studies by Taha et al. (2009) in The Lancet, Freedberg et al. (2020) in Gastroenterology, Janowitz et al. (2020) in Gut, Lu et al. (2007) in Crystal Growth & Design, and Kinoshita et al. (2005) in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

Chemical Structure and Mechanism of Action

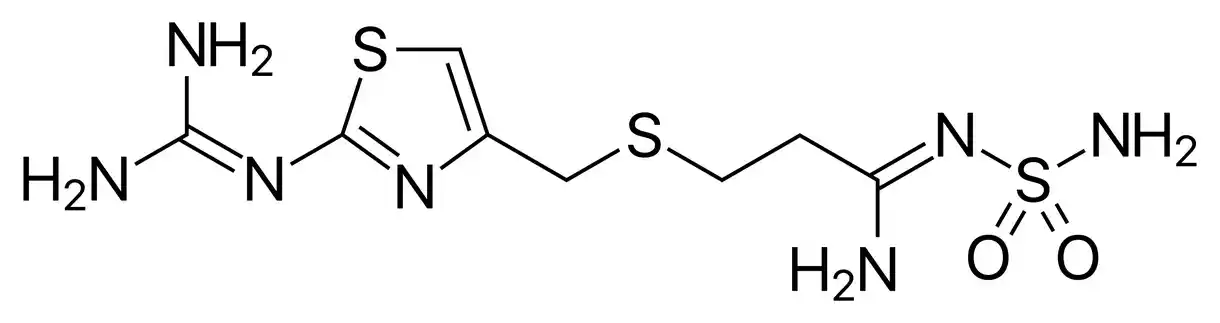

Famotidine is a white to light yellow crystalline substance that is also known by its chemical name, 3-[[[2-[(aminoiminomethyl)amino]-4-thiazolyl]methyl]thio]-N’-(aminosulfonyl)propanimidamide. Its molecular weight is 337.45 g/mol and its formula is C8H15N7O2S3. The thiazole ring in famotidine’s chemical structure is linked via a thioether bond to both a guanidine and a sulfamoyl group (Lu et al., 2007, “Polymorphism and crystallisation of famotidine”).

Famotidine functions as an H2RA, competitively inhibiting the histamine’s activity at the histamine-2 receptors on the stomach’s parietal cells. Famotidine lowers stomach acid production and secretion by inhibiting these receptors. With disorders like GERD and peptic ulcers, this mode of action aids in symptom relief and repair. Famotidine has no effect on other types of histamine receptors, such as those implicated in allergic responses, and is extremely selective for the histamine-2 receptors.

A phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (Taha et al., 2009, “Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial”) showed the effectiveness of famotidine in preventing peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin. Furthermore, a propensity score matched retrospective cohort study (Freedberg et al., 2020, “Famotidine use is associated with improved clinical outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients: a propensity score matched retrospective cohort study”) has shown that famotidine has been linked to better clinical outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients.

Indications

Famotidine is indicated for the treatment of various gastrointestinal conditions, including:

- Duodenal ulcers: Famotidine promotes healing and provides relief from symptoms associated with active duodenal ulcers.

- Gastric ulcers: The medication is effective in treating gastric ulcers and reducing the risk of recurrence.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): Famotidine helps manage symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn and acid regurgitation, and can prevent erosive esophagitis.

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: In patients with this rare condition, famotidine is used to control excessive gastric acid secretion caused by gastrinomas.

Contraindications and Precautions

- Hypersensitivity: Famotidine is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any of its components.

- Renal impairment: Caution should be exercised when administering famotidine to patients with renal insufficiency. Dosage adjustments may be necessary based on creatinine clearance.

- Hepatic impairment: Although no dosage adjustment is typically required in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment, cautious use is advised in those with severe liver dysfunction.

Special Warnings for the Elderly, Children, and Pregnant Women

- Elderly patients: Due to the potential for decreased renal function in elderly patients, lower doses or less frequent administration of famotidine may be required.

- Paediatric use: The safety and efficacy of famotidine in children under 12 years of age have not been established. Caution should be exercised when prescribing the medication to this age group.

- Pregnancy: Famotidine is classified as a pregnancy category B drug. While animal studies have not shown evidence of harm to the foetus, there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Famotidine should only be used during pregnancy if clearly needed.

- Breastfeeding: Famotidine is secreted in human breast milk. Nursing mothers should either discontinue the medication or stop breastfeeding, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

Dosage and Administration

The recommended dosage of famotidine varies depending on the condition being treated:

- Duodenal ulcers: 40 mg once daily at bedtime for 4-8 weeks.

- Gastric ulcers: 40 mg once daily at bedtime for 4-8 weeks.

- GERD: 20 mg twice daily for 6-12 weeks.

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Initially, 20 mg every 6 hours. Dosage can be increased to 160 mg every 6 hours as needed.

Famotidine can be taken with or without food. For optimal results, it is essential to follow the dosage instructions provided by the healthcare provider.

What Should I Do if I Miss a Dose of Famotidine?

If a dose of famotidine is missed, the patient should take it as soon as they remember, unless it is close to the time of the next scheduled dose. In such cases, the missed dose should be skipped, and the regular dosing schedule should be resumed. Patients should not take a double dose to compensate for a missed one, as this may increase the risk of side effects.

Uses

In addition to its primary indications, famotidine has been studied for various other uses:

- Prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin: Famotidine has been shown to reduce the risk of these complications in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (Taha et al., 2009, “Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial”).

- Treatment of functional dyspepsia: Famotidine, in combination with mosapride and tandospirone, has been investigated for the management of functional dyspepsia (Kinoshita et al., 2005, “Effects of famotidine, mosapride and tandospirone for treatment of functional dyspepsia”).

- COVID-19 treatment: Recent studies have explored the potential of famotidine in improving clinical outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients (Freedberg et al., 2020, “Famotidine use is associated with improved clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a propensity score matched retrospective cohort study”) and in non-hospitalised patients (Janowitz et al., 2020, “Famotidine use and quantitative symptom tracking for COVID-19 in non-hospitalised patients: a case series”).

Overdose

In case of a famotidine overdose, patients may experience the following symptoms:

- Dizziness and headache

- Confusion and disorientation

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhoea and abdominal pain

- Tachycardia and hypotension

Treatment of a famotidine overdose typically involves supportive care, including monitoring of vital signs and administration of intravenous fluids if necessary. In severe cases, hospitalisation may be required. There is no specific antidote for famotidine overdose, and haemodialysis is not likely to be effective due to the drug’s high protein binding.

Famotidine Side Effects

While famotidine is generally well-tolerated, some patients may experience side effects. These can range from mild to severe and may vary in frequency.

Common Famotidine Side Effects

The most common side effects associated with famotidine use include:

- Headache and dizziness

- Constipation or diarrhoea

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain or discomfort

- Dry mouth and taste disturbances

These side effects are usually mild and tend to resolve on their own without the need for medical intervention. However, if they persist or become bothersome, patients should consult their healthcare provider.

Rare but Possible Famotidine Side Effects

Some less common side effects of famotidine may include:

- Skin rash, itching, or hives

- Fatigue and weakness

- Muscle or joint pain

- Anxiety and depression

- Insomnia and sleep disturbances

If patients experience any of these side effects, they should notify their healthcare provider for appropriate management.

Serious Famotidine Side Effects

In rare cases, famotidine may cause severe side effects that require immediate medical attention. These include:

- Anaphylaxis or severe allergic reactions, characterised by difficulty breathing, swelling of the face, lips, tongue, or throat, and severe itching or hives

- Agranulocytosis, a condition in which the body produces insufficient white blood cells, leading to an increased risk of infections

- Pancytopenia, a deficiency of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- Liver dysfunction, indicated by yellowing of the skin or eyes, dark urine, and upper abdominal pain

Patients who experience any of these serious side effects should seek emergency medical care.

Interactions

Famotidine may interact with other medications or substances, potentially altering its effectiveness or increasing the risk of side effects.

Drug-Drug Interactions

Notable drug-drug interactions with famotidine include:

- Antacids: Concomitant use of famotidine with antacids may decrease the absorption of famotidine. Patients should take famotidine 1-2 hours before or after antacid administration.

- Probenecid: Co-administration of famotidine with probenecid may increase famotidine levels in the body, potentially leading to an increased risk of side effects.

- Atazanavir: Famotidine may reduce the absorption and effectiveness of atazanavir, an antiretroviral medication used to treat HIV.

Patients should inform their healthcare provider about all medications they are taking to avoid potential drug interactions.

Drug-Food Interactions

Famotidine can be taken with or without food. However, patients should be aware that taking famotidine with food may slow down its absorption and delay its onset of action. If rapid symptom relief is desired, famotidine should be taken on an empty stomach. Patients should also avoid consuming alcohol while taking famotidine, as it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal side effects and potentially worsen existing digestive conditions.

Additional Important Information

Resistance Development

Since famotidine acts on histamine-2 receptors rather than directly influencing bacterial growth or survival, resistance to the medication is thought to be uncommon. On the other hand, prolonged famotidine treatment may alter the gut microbiota and perhaps promote the expansion of bacterial strains that are resistant to the medication. This change in gut flora may have an indirect role in the emergence of diseases resistant to antibiotics, especially in hospitalised patients or those with weakened immune systems. It is advised to regularly monitor patients receiving extended famotidine medication in order to identify any potential changes in the gut flora and to address any issues with the development of resistance.

Preclinical and Clinical Studies

A plethora of preclinical and clinical investigations have been carried out to assess the pharmacological characteristics, safety, and effectiveness of famotidine. Taha et al. looked into the use of famotidine in a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to prevent peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients receiving low-dose aspirin. According to the research, “Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial,” famotidine successfully decreased the study population’s chance of developing these problems.

The possible use of famotidine in the treatment of COVID-19 has also been investigated in recent research. In a propensity score matched retrospective cohort analysis, Freedberg et al. discovered that the use of famotidine was linked to better clinical outcomes among COVID-19 hospitalised patients. The study, which was published in the journal Gastroenterology, emphasised the necessity of more investigation to validate these results and clarify the underlying mechanisms of action.

Janowitz et al. examined the use of famotidine and quantitative symptom tracking for COVID-19 in out-of-hospital patients in a case series that was published in Gut. The research shed light on famotidine’s possible function in controlling COVID-19 mild to moderate sufferers’ symptoms and illness development.

Famotidine’s crystallisation and polymorphism features have also been investigated since changes in these attributes may affect the drug’s solubility, stability, and bioavailability. The polymorphism and crystallisation behaviour of famotidine were thoroughly studied by Lu et al., yielding important insights for the creation of stable and efficient formulations.

Moreover, famotidine has been studied in conjunction with other medications to treat functional dyspepsia. The potential advantages of combination treatment in the management of functional dyspepsia were demonstrated by Kinoshita et al.’s evaluation of the effects of famotidine, mosapride, and tandospirone in patients with this disease.

Our knowledge of the pharmacological uses, safety profile, and physicochemical characteristics of famotidine has substantially benefited from these preclinical and clinical investigations. Research is still being done to find new uses for this useful drug and improve its application in therapeutic settings.

Post-authorization Studies and Pharmacovigilance

Famotidine was first approved, and a number of post-authorization studies were carried out to evaluate its safety and effectiveness in different patient demographics and therapeutic contexts. These studies are essential to the ongoing pharmacovigilance initiatives, which track and assess the medication’s long-term safety profile. One such research examined the effects of famotidine in combination with mosapride and tandospirone for the treatment of functional dyspepsia; it was published in the journal Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics by Kinoshita et al. The results of this study advance our knowledge of the possible advantages and disadvantages of famotidine usage in this particular patient population.

Ever since famotidine was first brought to market, pharmacovigilance efforts have continued, involving the gathering and examination of adverse event data. These initiatives have aided in the discovery of uncommon but potentially dangerous side effects that were missed in the early clinical studies, such pancytopenia and agranulocytosis. The safety profile of famotidine is continuously monitored to make sure patients and healthcare professionals are aware of any new dangers and may use the drug with knowledge.

Pharmacokinetic Characteristics

The unique pharmacokinetic characteristics of famotidine contribute to both its safety and therapeutic success. After oral administration, the medication is quickly absorbed from the digestive system and reaches peak plasma concentrations in one to three hours. The bioavailability of famotidine ranges from 40 to 45 percent, and meal consumption has no discernible impact on this value. The medication is largely excreted unaltered by the kidneys and has very little hepatic metabolism. Famotidine has an elimination half-life of 2.5 to 3.5 hours in healthy persons; however, in patients with renal impairment, this half-life may be extended and dose modifications may be necessary.

Famotidine’s pharmacokinetic characteristics have been thoroughly investigated in a range of patient populations, including young children, the elderly, and those with liver or kidney disease. In order to guarantee the best possible treatment results and reduce the chance of side effects, these studies have shed important light on the necessity for dosage modifications and monitoring in particular groups. The polymorphism and crystallisation behaviour of famotidine were thoroughly analysed by Lu et al.; this work has significant ramifications for the creation of stable and bioavailable medicinal formulations.

Comparative Efficacy

The effectiveness of famotidine in comparison to other proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonists has been assessed. Famotidine has generally been shown to be equally effective as other H2RAs, like cimetidine and ranitidine, in treating peptic ulcers, GERD, and other conditions linked to acid reflux. But in some cases, especially when treating severe erosive esophagitis and curing Helicobacter pylori infection, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have shown to be more effective.

Famotidine is still a valuable treatment choice for many patients despite the benefits of PPIs in some situations. This is because it has a better safety profile and a reduced risk of medication interactions than certain PPIs. Individual patient considerations, such as the degree of symptoms, underlying medical problems, and possibility of medication interactions, should be taken into consideration while choosing between famotidine and other acid-suppressive drugs.

The comparative effectiveness of famotidine in the context of treating COVID-19 has also been investigated in recent research. In a propensity score matched retrospective cohort analysis, Freedberg et al. hypothesised that among hospitalised COVID-19 patients, famotidine usage was linked to better clinical outcomes than non-use. To validate these results and determine famotidine’s place in COVID-19 treatment, more investigation is necessary.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

The existing data on the effectiveness and safety of famotidine in many clinical situations has been synthesised in large part through the use of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These studies combine data from several original research studies to present an extensive and objective evaluation of the drug’s effectiveness. For example, a systematic review conducted by Taha et al. and published in The Lancet assessed the efficacy of famotidine in preventing oesophagitis and peptic ulcers in individuals who were on low-dose aspirin. Data from the phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled FAMOUS trial were included in the review. The results of this systematic analysis provide evidence for the preventive use of famotidine in individuals who may experience gastrointestinal problems associated to aspirin.

Freedberg et al.’s investigation of the relationship between famotidine use and better clinical outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients is another instance of a meta-analysis including the drug. The authors were able to offer a more thorough evaluation of the possible advantages of famotidine in this patient population by combining data from many observational trials. However, because the included studies were observational in nature and there might be confounding variables, the authors advised that the results should be read cautiously.

The effectiveness and safety of famotidine in relation to other acid-suppressive medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and other H2RAs, have also been compared using systematic reviews and meta-analyses. By offering a more thorough knowledge of the relative advantages and disadvantages of certain drugs in various patient demographics and treatment situations, these studies have aided in the making of therapeutic decisions.

Current Research Directions and Future Perspectives

The examination of novel therapeutic indications, the enhancement of drug delivery methods, and the study of plausible mechanisms of action are the main focuses of current famotidine research. The use of famotidine in the treatment of COVID-19 is one potential field of study. Although preliminary observational studies, such those conducted by Freedberg et al. and Janowitz et al., have shown some advantages, randomised controlled trials are presently in progress to offer more conclusive proof on the effectiveness and safety of famotidine in this particular situation.

The creation of innovative famotidine medication delivery methods and formulations is a current research focus. Enhancing the medication’s bioavailability, stability, and patient adherence are the goals of these initiatives. To improve famotidine’s treatment efficacy, for instance, scientists are looking into the use of transdermal patches, oral disintegrating tablets, and formulations based on nanoparticles.

Apart from the clinical research endeavours, current preclinical investigations are examining the possible modes of action of famotidine that extend beyond its proven function as an H2RA. The drug’s potential advantages in disorders like COVID-19 may be attributed to its effects on immunological regulation, inflammation, and viral replication, all of which are being studied in these trials.

It is anticipated that famotidine research will keep developing and growing in the future. Famotidine’s possible impacts on a wider spectrum of medical problems may be examined when new therapeutic targets and disease pathways are discovered. Furthermore, improvements in personalised medicine techniques and drug delivery technology could make it possible to create famotidine-based treatments that are more precise and successful.

To guide future research efforts and transfer discoveries into better patient care, industry partners, doctors, and researchers must work together. Through the utilisation of novel technologies and research approaches, in addition to expanding upon the current body of information, scientists may further explore the complete therapeutic range of famotidine and maximise its application in clinical settings.

In Brief

Histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) like famotidine are used to treat and prevent a number of gastrointestinal disorders, including Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, GERD, and peptic ulcers. The use of famotidine has been discussed in this article along with its side effects, interactions, warnings, and dosage. It has been discussed that elderly patients, youngsters, and women who are pregnant or nursing should receive special attention. Famotidine’s pharmacokinetic characteristics, mechanism of action, and comparative effectiveness with other acid-suppressive drugs have all been studied. The significance of keeping an eye on the drug’s safety profile has been emphasised by post-authorization studies and continuing pharmacovigilance initiatives. The possible application of famotidine in the treatment of COVID-19 and the creation of innovative drug delivery methods are examples of current research areas that have been proposed. Future views on the changing field of famotidine research have been taken into account, highlighting the necessity of industrial partners, physicians, and researchers working together to maximise the therapeutic potential of this important drug.

ATTENTION: It is crucial never to take medication without a qualified doctor’s supervision. Always read the Patient Information Leaflet (PIL) with each prescribed medicine. Pharmaceutical companies accurately describe each product’s details, which may be regularly updated, though variations may exist depending on the drug’s composition. This article analyses the active ingredient rather than specific brand names containing this generic medicine worldwide. Study the instruction leaflet for each preparation you use. Close cooperation with your doctor and pharmacist is vital. Self-administering medication carries serious health risks and must be strictly avoided.

Bibliography

- Freedberg, D. E., Conigliaro, J., Wang, T. C., Tracey, K. J., Callahan, M. V., Abrams, J. A., & Famotidine Research Group. (2020). Famotidine use is associated with improved clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A propensity score matched retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. gastrojournal

- Janowitz, T., Gablenz, E., Pattinson, D., Wang, T. C., Conigliaro, J., Tracey, K., & Tuveson, D. (2020). Famotidine use and quantitative symptom tracking for COVID-19 in non-hospitalised patients: a case series. Gut, 69(9), 1592-1597. gut.bmj

- Kinoshita, Y., Hashimoto, T., Kawamura, A., Yuki, M., Amano, K., Sato, T., … & Chiba, T. (2005). Effects of famotidine, mosapride and tandospirone for treatment of functional dyspepsia. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 21, 37-41. onlinelibrary

- Lu, J., Wang, X. J., Yang, X., & Ching, C. B. (2007). Polymorphism and crystallization of famotidine. Crystal growth & design, 7(9), 1590-1598. pubs.acs

- Taha, A. S., McCloskey, C., Prasad, R., & Bezlyak, V. (2009). Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet, 374(9684), 119-125. thelancet